As an educator I’ve always believed that schools determine culture. In my book, “St. Louis School Desegregation: Patterns of Progress and Peril,” I use St. Louis school history to illustrate this point. Many find it shocking to learn that St. Louis and its surrounding counties evaded effective desegregation until the 1980s.

In this research I explore the ways that “soft racism” has been employed historically in Missouri that allowed school segregation to persist for so long, and how that racism has shaped contemporary culture. The school desegregation lawsuit, Liddell v. Board of Education, St. Louis (1972) serves as the pivotal event that illuminates the ways that racism worked to deny education to black students in St. Louis. The opposition to school desegregation exemplified soft racism.

Unlike the Deep South and northern cities, like Boston, there was relatively little violence that accompanied school desegregation in St. Louis. Instead, Missourians employed a rather dignified disdain for blacks by writing letters to protest desegregation and voicing their opposition in school board meetings. Those who equated racism with violence expressed the view that states’ rights, individual choice, and prohibitive cost were the true motives for desegregation opposition. I suggest that racism was the true motive and that a re-examination of the soft ways that racism has historically been expressed in Missouri would shine a light on the desegregation battle.

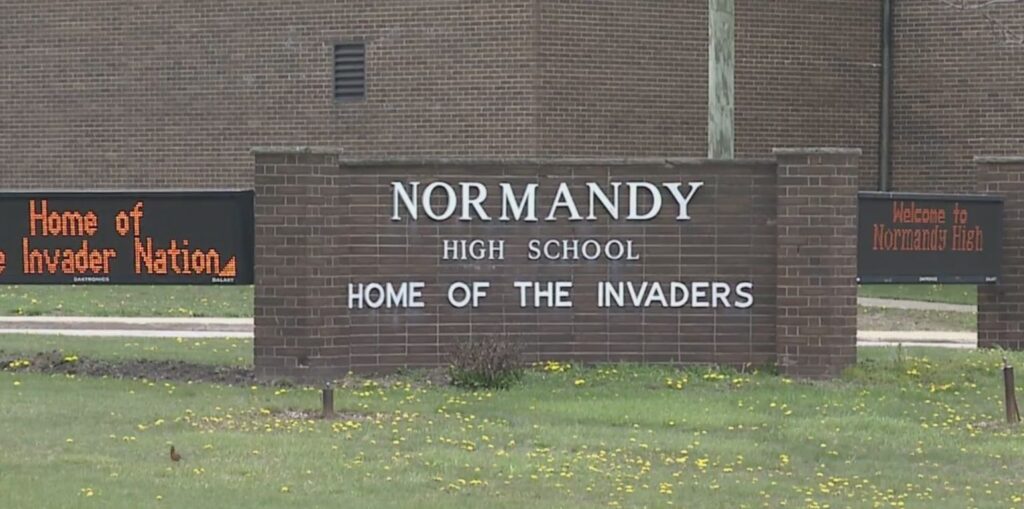

In 1983, St. Louis counties were forced to participate in a city-to-county transfer program in which black students from segregated, urban schools would be bused to predominately white, suburban schools. Ratios of black students were used as a guides to indicate desegregation. This worked for most suburban districts that have historically enrolled few to no black students. There were, however, three predominately black, suburban school districts that could already meet the quota for black students that had been set by policy makers. One of those school districts was Normandy School District. Normandy High School was thrust into the spotlight in 2014 when a recent graduate, Michael Brown, was shot and killed by a police officer who had grown up in a predominately white suburb of St. Louis.

I argue that the death of Michael Brown is the worst-case scenario that results from desegregation. Neither the police officer nor the teen victim had been given the opportunity to learn how to have meaningful interactions with people outside of their community. School desegregation should have occurred in American schools in 1954, yet these two, who were both under the age of 30, had spent their lives in segregated communities.

This book offers a broad look at Missouri history and the role that the state has played as a racial standard-bearer for the country. In addition, it offers an examination of soft racism and the varied ways that racism was employed to oppose desegregation. It uses the 1972 lawsuit filed by Minnie Liddell to show how school segregation in St. Louis was largely dismantled and profiles several key actors, including two women, who played critical roles in creating a large-scale desegregation program. The book ends with the assertion that desegregation policy did not go far enough. Normandy high school and its black, suburban counterparts are proof.

Teachers, Education faculty, and school policy makers will find this research useful as a tool to help navigate discussions about the nuances of racism and how it is expressed. For those who believed that we were a post-racial society, this book offers a critical look at the ways that racism has been subtly but powerfully used over time. It implores readers to reconsider how we navigate school policy to shape American culture in more positive ways.

Repost from: https://www.palgrave.com/gp/blogs/social-sciences/hope-rias